Cite this problem as Problem 48.

Problem

![]() -routing is a distributed task involving two players, Alice and Bob, who co-operate to redirect a quantum system

-routing is a distributed task involving two players, Alice and Bob, who co-operate to redirect a quantum system ![]() based on the value of classical inputs

based on the value of classical inputs ![]() . Given a Boolean function

. Given a Boolean function ![]() , an

, an ![]() -routing protocol has the following communication pattern:

-routing protocol has the following communication pattern:

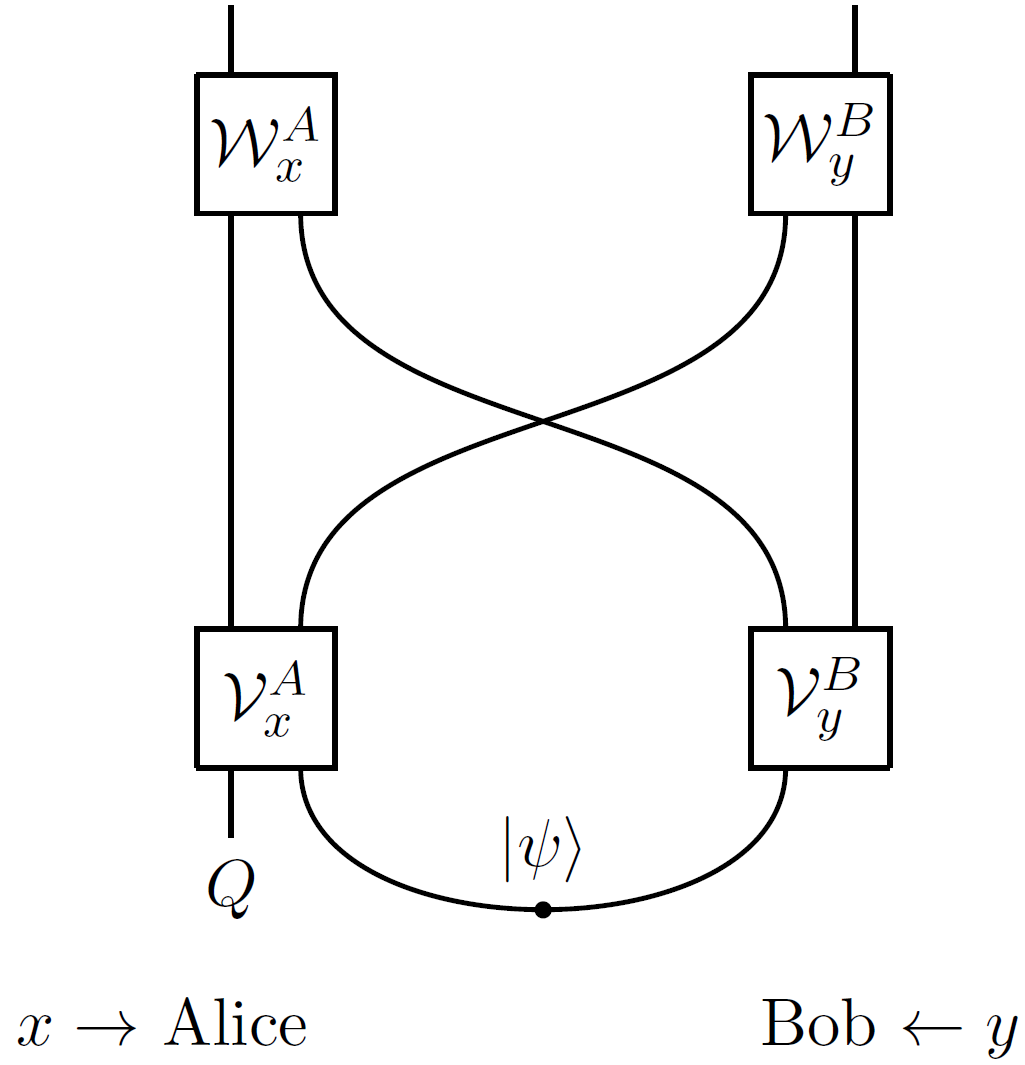

The diagram should be read from bottom to top. The lower curved wire represents an initial shared entangled state ![]() held between Alice and Bob: the logarithm of its local dimension is the entanglement cost of the protocol. After receiving input

held between Alice and Bob: the logarithm of its local dimension is the entanglement cost of the protocol. After receiving input ![]() , Alice performs the quantum operation

, Alice performs the quantum operation ![]() on both system

on both system ![]() and her part of the shared entangled state. This operation outputs two quantum systems, one of which she sends to Bob. Similarly, upon receiving input

and her part of the shared entangled state. This operation outputs two quantum systems, one of which she sends to Bob. Similarly, upon receiving input ![]() , Bob implements the quantum operation

, Bob implements the quantum operation ![]() on his part of the state, which also outputs two quantum systems, one of which he sends to Alice. Alice then implements the operation

on his part of the state, which also outputs two quantum systems, one of which he sends to Alice. Alice then implements the operation ![]() on her remaining quantum system and the quantum system she receives from Bob; similarly, Bob implements the operation

on her remaining quantum system and the quantum system she receives from Bob; similarly, Bob implements the operation ![]() on his remaining quantum system and the system he receives from Alice.

on his remaining quantum system and the system he receives from Alice.

Let ![]() denote the identity channel on system

denote the identity channel on system ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() (

(![]() ) denote the induced quantum channel from

) denote the induced quantum channel from ![]() to Alice’s (Bob’s) final system. The

to Alice’s (Bob’s) final system. The ![]() -routing protocol is correct if, for all

-routing protocol is correct if, for all ![]() with

with ![]() , it holds that

, it holds that ![]() ; and, for all

; and, for all ![]() with

with ![]() , it holds that

, it holds that ![]() . At the end of a correct

. At the end of a correct ![]() -routing protocol, the initial quantum state of system

-routing protocol, the initial quantum state of system ![]() will hence end up at Alice’s or Bob’s lab depending on the value of

will hence end up at Alice’s or Bob’s lab depending on the value of ![]() .

.

For ![]() , the

, the ![]() -routing protocol is

-routing protocol is ![]() -sound if

-sound if

![]()

![]()

where ![]() denotes the diamond norm.

denotes the diamond norm.

Question: For fixed ![]() , find a sequence of explicit Boolean functions

, find a sequence of explicit Boolean functions ![]() , with

, with ![]() , for which the minimum entanglement cost of an

, for which the minimum entanglement cost of an ![]() -sound

-sound ![]() -routing protocol scales as

-routing protocol scales as ![]() .

.

Background

The ![]() -routing task was introduced in the quantum position-verification setting [1, 2]. In that context, proving an entanglement lower bound on

-routing task was introduced in the quantum position-verification setting [1, 2]. In that context, proving an entanglement lower bound on ![]() -routing establishes the security of a quantum position-verification scheme. This scheme has the property that an honest player performs nearly only classical operations: they compute

-routing establishes the security of a quantum position-verification scheme. This scheme has the property that an honest player performs nearly only classical operations: they compute ![]() and then redirect

and then redirect ![]() based on the outcome. Meanwhile, it is hoped that the dishonest player (who uses the non-local quantum computation model) needs entanglement that grows with

based on the outcome. Meanwhile, it is hoped that the dishonest player (who uses the non-local quantum computation model) needs entanglement that grows with ![]() , preferably polynomially. It was also shown that several other proposals for quantum position-verification are equivalent to

, preferably polynomially. It was also shown that several other proposals for quantum position-verification are equivalent to ![]() -routing, in the sense that entanglement cost across all these settings are all related polynomially. Thus, good

-routing, in the sense that entanglement cost across all these settings are all related polynomially. Thus, good ![]() -routing lower bounds are a necessary step to establishing the security of many QPV schemes.

-routing lower bounds are a necessary step to establishing the security of many QPV schemes.

In [3], it was observed that ![]() -routing is closely related to the \emph{conditional disclosure of secrets} primitive studied in information-theoretic classical cryptography. In particular, it was shown that the randomness cost in CDS for a function

-routing is closely related to the \emph{conditional disclosure of secrets} primitive studied in information-theoretic classical cryptography. In particular, it was shown that the randomness cost in CDS for a function ![]() , call it

, call it ![]() , upper bounds the entanglement cost in

, upper bounds the entanglement cost in ![]() -routing for the same function,

-routing for the same function, ![]() ,

,

![]()

Thus, poly![]() lower bounds on entanglement in

lower bounds on entanglement in ![]() -routing would imply poly

-routing would imply poly![]() lower bounds on randomness in CDS. Obtaining such CDS lower bounds has been identified as an important open problem in classical cryptography [4].

lower bounds on randomness in CDS. Obtaining such CDS lower bounds has been identified as an important open problem in classical cryptography [4].

![]() is also known to be upper bounded by the size of a secret sharing scheme with indicator function

is also known to be upper bounded by the size of a secret sharing scheme with indicator function ![]() , and by the size of a span program computing

, and by the size of a span program computing ![]() [5]. Hence,

[5]. Hence, ![]() -routing lower bounds also lower bound these settings.

-routing lower bounds also lower bound these settings.

Partial Results

The work of [6] proved linear lower bounds on ancilla size for random functions. There are also some restrictions on the model, which takes Alice and Bob’s actions to be unitary.

In [7], linear lower bounds on entanglement for several explicit functions in the case where the ![]() -protocol is perfect in either

-protocol is perfect in either ![]() or

or ![]() instances are derived. The technique is based on the non-deterministic rank of the specified function.

instances are derived. The technique is based on the non-deterministic rank of the specified function.

For CDS, logarithmic lower bounds are proven in [8]. These were adapted to quantum CDS in [9].

References

[1] A. Kent, W. J. Munro, and T. P. Spiller, Physical Review A, 84(1):012326 (2011).

[2] H. Buhrman, S. Fehr, C. Schaffner, and F. Speelman. The garden-hose model. In Proceedings of the 4th conference on Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science, pages 145–158, (2013).

[3] R. Allerstorfer, H. Buhrman, A. May, F. Speelman and P. V. Lunel, Quantum, 8:1387, (2024).

[4] Benny Applebaum and Prashant Nalini Vasudevan. Placing conditional disclosure of secrets in the communication complexity universe. Journal of Cryptology, 34(2):11, (2021).

[5] Y. Gertner, Y. Ishai, E. Kushilevitz, and T. Malkin. Protecting data privacy in private information retrieval schemes. In Proceedings of the thirtieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, pages 151–160, (1998).

[6] A. Bluhm, S. Höfer, A. May, M. Stasiuk, P. V. Lunel, and H. Yuen, arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.23893.

[7] V. R Asadi, E. Culf, and A. May, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.18647.

[8] R. Gay, I. Kerenidis, and H. Wee. Communication complexity of conditional disclosure of secrets and attribute-based encryption. In Annual Cryptology Conference, pages 485–502. Springer (2015).

[9] V. R. Asadi, K. Kuroiwa, D. Leung, A. May, S. Pasterski, and C. Waddell, Quantum, 9:1885 (2025).